MUERTE Y MARIPOSAS (DEATH & BUTTERFLIES): A PERSONAL JOURNEY

My desire to see the overwintering monarchs began well before Marc suddenly died. But it wasn’t until a year after his death that I felt an urgent need to experience the monarch migration before these beloved insects disappeared from our landscapes forever.

Contemplating death and my own mortality—while armed with a newly acquired sense of fearlessness—I packed up some stuff and journeyed to Central Mexico.

Macheros, gateway to Cerro Pelón

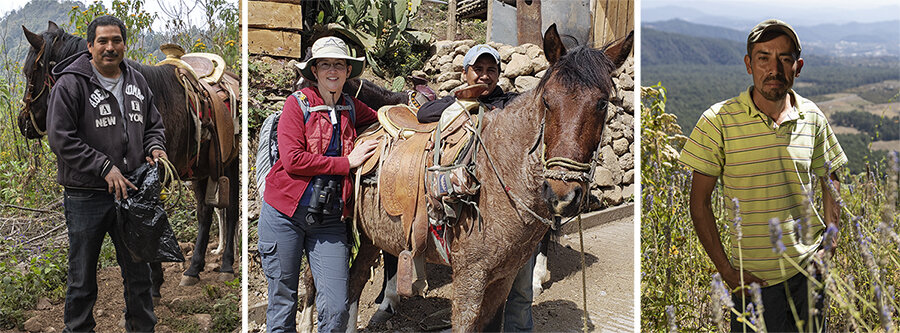

The small village of Macheros lies within the State of Mexico and is the home of a little over 300 residents. It’s a welcoming place, with many beautiful and friendly faces, and it’s there that I made my four-day stay. I had decided on the quaint JM’s Butterfly B&B after reading their website’s page “How to Help Monarchs.” I instantly admired this small family owned eco-tourism operation that helps to protect the monarchs’ habitat by investing in the community. Tourist pesos remain in the village through the sourcing of locally grown foods and from employing residents: from lodging and restaurant staff to hiking guides and the local vaqueros and their horses.

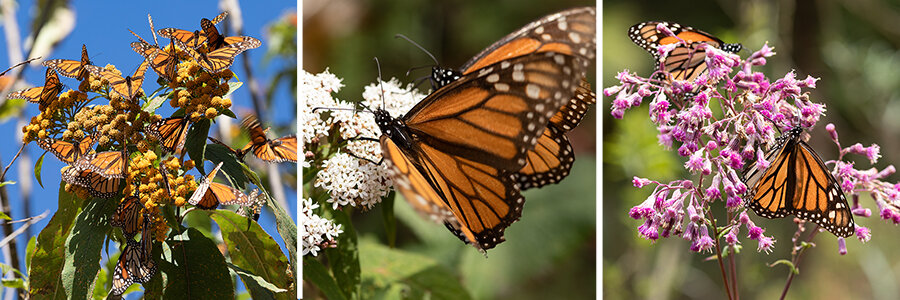

It was time to see the butterflies. I perched uncomfortably on a small brown horse named Rocío at the upper edge of town, the high-altitude forest of Cerro Pelón sprawling before me. Led by her handler, Javier, Rocío carried me up up up and into a clearing with other turistas close behind. This was my first major sighting, the place where those butterflies, in the warmth of the late morning sunlight, left the trees and took wing to explore the area. They flapped. They soared. They puddled on grassy ground by the hundreds and nectared on native wildflowers.

The moment was powerful, yet peaceful.

this was my second day of horseback riding.

Ellen and Joel of JM’s established a nonprofit that currently pays four residents from the town to patrol the Cerro Pelón forest.

Although poaching still exists, these four arborists have been successful in deterring much of the illegal logging of firs

and pines, the mariposa monarca’s essential roosting trees.

Beautiful moss-covered trees in the forest.

Generation Super

Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve sign on the way to JM’s.

The dense forest in the State of Michoacán.

When the days grow warm with the arrival of spring, these super gen butterflies will depart the safety of Mexico’s forests and begin their way north, staying east of the Rockies. It could take up to five generations before the next super generation is born; the monarchs we see feeding, mating and laying eggs here in the Mid-Atlantic in early summer are most likely another generation of monarchs traversing north. As the days become shorter and cooler and native milkweed foliage fades, another super generation is triggered and the butterflies head south again. It’s easy to see why what we plant on our own properties can fundamentally dictate the life or death of our monarchs.

Salvia mexicana, Ageratina altissima and Salvia gesneriiflora. iNaturalist is a great tool for identifying the flowers I came across while hiking.

The diverse amounts of flowering plants growing along the mountain trails supply fuel for the monarchs when they are active. What looked like Salvia stood brilliantly in candy-colored drifts along the open forest edges; they were blue, red, violet and a dark rosey-purpley color I’d last seen in a Chiclets palette. Many other wildflowers and even some woody shrubs were in bloom; their cheerful clusters gently nodded with the weight of hungry monarchs.

Monarchs feasting.

Meanwhile, back in Macheros

Whenever I had an opportunity, I’d wander the streets surrounding JM’s. In the morning, the village kids, all dressed in their uniforms, streamed in small pods toward the only school. The women efficiently went about their domestic chores, and the men who were guides that day readied their horses for an outing with butterfly enthusiasts. I would receive a warm “buenos días” in return to my own cheerful greeting. Meandering about the village were free-range dogs, clucky chickens and even some wild turkeys. I saw one wild mammal during my roamings: a tree squirrel. I’m guessing the little guys were being hunted to extirpation just like the deer have been.

Spotting that timid squirrel bought me back to the squirrels at home who were much less fearful and considerably more plentiful. Our squirrels had been a daily source of amusement for Marc and me, and for many years we enjoyed observing their wacky antics together. My former United States Marine would playfully name the lovable rodents by their physical traits, an endeavor which was altogether endearing. “Chubba,” “One Eye,” “Hipster,” “Ginger,” “Shirley.” Shirley …? Marc shrugged and said with a grin, “She just looks like a Shirl.” And then one day, because time keeps moving forward, I realized that all the squirrels that had known Marc were no longer around.

She lived in our neighborhood for three years.

At the end of an emotive day of visiting monarchs, I would chat with the other guests lounging about the B&B. Most of these interesting folks hailed from Canada and the United States. They were naturally curious people who enjoyed traveling and couldn’t get enough of the butterflies. A few had raised monarchs at home or in schools; some had planted loads of milkweed in their gardens. One well-meaning woman from Maryland proudly informed me she had just planted a butterfly bush, and well … I never could pass up a teaching moment. We possessed a collective appreciation of earth’s natural wonders—and I soon discovered that refreshing margaritas and home-made chips with guacamole were another common bond.

Were we all drawn to the butterflies for the same reason?

I shouldn’t have been surprised to meet four other widows at different points during my stay, all of them traveling with friends or family. We were close in age, and I guessed the other gals were in their late 50s to mid 60s. Widows need to talk about their loved ones—something I’d urgently felt since that tragic day when Marc died—so conversations about death came naturally. We easily discussed our losses, shared sorrowful tears, and confessed to how we were or were not progressing. Cancer, faulty hearts, suicide … our spouses’ deaths were as individual and as complicated as our grief.

The only material I could read in those early days of despair were the nonfiction books on coping my sister and friends had given me. Most of the authors noted that it’s typical for those traumatized by the death of a loved one to abandon thoughts of their personal well-being. This did apply to me and still stands. It’s not that I’m suicidal or reckless; I just don’t worry about what happens to me. I also find that the truly insignificant doo-doo that life has thrown and will continue to throw my way is not worthy of my energy. Huge inconveniences have become insignificant. What once made me squirm or fearful no longer does. To this point, Judy, a recent widow whose husband died a month after Marc did, said she is no longer afraid of flying. Donating blood hadn’t been an option for me—needles and I have never been compatible—but I now do so regularly. Dauntless, I knew that traveling solo to the heart of Mexico with a zero command of the Spanish language would not be a concern.

So. Many. Butterflies.

The next to the last day of my travels was Valentine’s Day, Marc’s birthday, and it was on this significant day that I found myself at the famous El Rosario sanctuary. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to sprinkle the small amount of Marc’s cremated remains that I had brought with me in such an accessible, trail-paved and touristy site. But this forest was decidedly beautiful and the day sunny and warm, conditions that coaxed thousands of butterflies into flight. And when I learned that the monarchs were quite abundant this winter, and had roosted low in the forest where they were even more visible—the likes of which have not been seen in 15 years—I decided yes, it would be okay.

What is the meaning of life?

The death of a life-partner ultimately forces one to consider what’s most important. With death, priorities, material possessions and even friendships are reevaluated. What is the true meaning of life? I’ve Googled that question often—with no clear answer ever appearing.

I often think about the now-dated 70’s sci-fi movie “Soylent Green” and the looming death of the Edward G. Robinson character, Sol. In this cautionary tale, an aging Sol decides to end a difficult life by admitting himself into a euthanasia facility. While dying, he is soothed by IMAX-sized images of nature unfolding, because, in this particular future of 2022, there isn’t any nature left. Dramatic orange sunsets, rippling streams, verdant forests … those are the last images that Sol chooses to experience. Surely the filmmakers were also ecologists.

Indeed, nature is the key to reparation and spiritual attainment; it’s our life-force connection to all the universe. Nature is comforting. It is also healing.

“do the right thing”

Alas, we possess little to no power in controlling death. This is a truth I’m continuing to struggle with. “If only I had …” If only. Individually, we have zero control over so many things, large-scale environmental issues among them; however, finding the things I do have control over is how I live and cope.

The power to directly aid our wild creatures is completely mine to wield.

Marc was an extraordinary being and believed we should just “do the right thing.” And treading lightly on the environment was one of the things we had practiced together. Do we not have the responsibility to leave as small a footprint on earth as we can? To be grand stewards of our land? To ultimately help ourselves? It’s not difficult to do.

I continue to grieve for a man who, when his heart failed at 52 years of age, had his future stolen. It’s been a surreal journey not only for me but also for Marc’s family and friends; a darkness impossible to comprehend unless you’re in it. The support I’ve received from loved ones and the other widows I’ve befriended through the Washington Regional Transplant Community has been truly amazing. I am forever grateful.

Thank you also to those kind widows who experienced the monarch phenomenon, for opening themselves up to me; and to the impoverished yet insightful people of Macheros, for doing the right thing.

And then there are the butterflies; those enchanting preternatural insects with the mystifying migration. Were they just a momentary distraction from my new reality? No, I don’t think so. I can feel that they brought some much-needed relief to my perpetually aching heart.

Godspeed little monarchs.