Anatomy of a Curbside Planting

There I was… the sun shining, my windows down… just innocently cruisin’ along. Then it happened: The drive-by double take. Not surprisingly, only a native planting could grab my attention that way.

Yessiree, excitement reigns when I come across these non-traditional gardens: the gardens that keep on giving. And I’m equally thrilled to report that I’ve been seeing these native plantings sprouting up more and more.

Eye Catching Corner

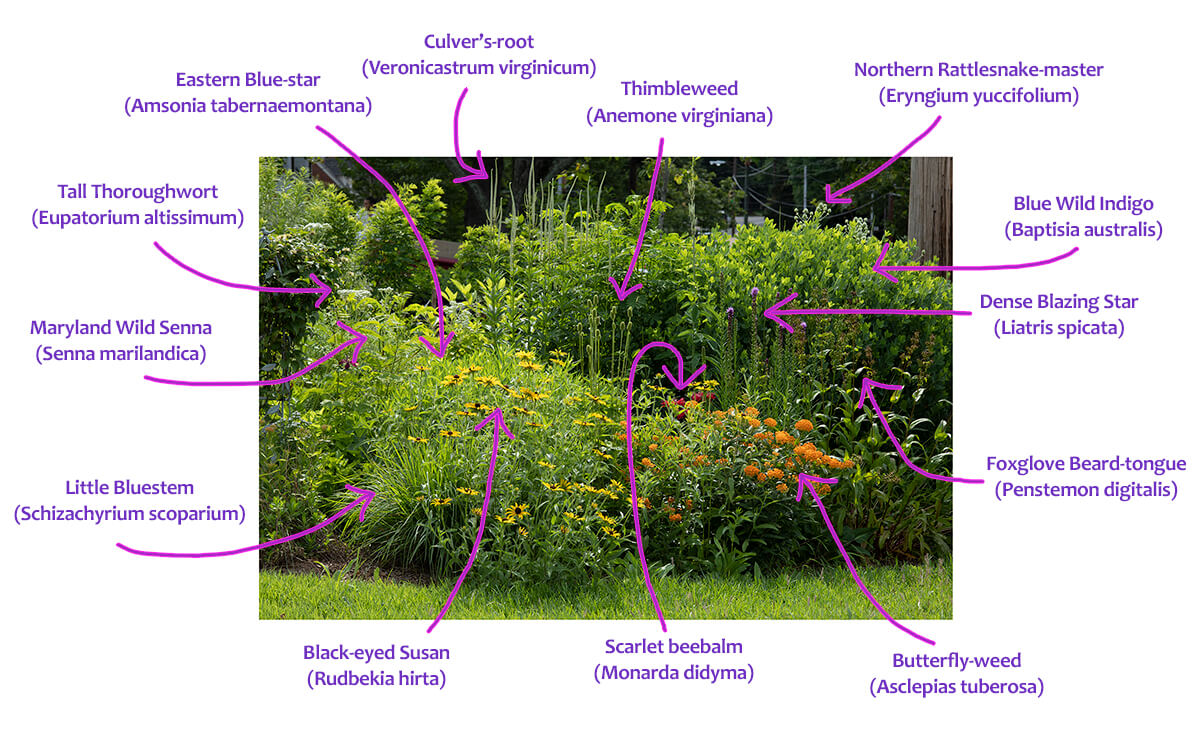

This native plant collection stood boldly at a residential cross street curb. What really made it pop was its fun and eclectic assortment of straight species. (I spy zero cultivars!) There were plants of varying heights, leaf types and flower hues—all wrapped up in an outstanding design.

Luckily, I was passing through this Arlington, Virginia, neighborhood in June. I mention the month because I think early summer shows off native gardens best. Everything is upright and perky, a number of plants are blooming and foliage is exceptionally fresh and green. It’s a glorious time.

Naturally I wanted to know more about this landscape. The gardener of the house, Rob Iera, kindly responded to the note I left at his door and we soon chatted about his enthusiasm for native plants.

A Rare Breed of Gardener

Rob, I learned, is a second-generation native plant gardener; so rare a breed, he’s the first I’d ever met. “My aunt and uncle have been involved in the native plant community in York, Pennsylvania, for over 30 years,” he explained. “My mom picked up an interest for her gardens from my aunt, and I gravitated to natives, too!”

How awesome is that?

Having grown up around Pennsylvania’s indigenous plants and then lived and gardened in Michigan for a bit, Rob has embraced the challenge of learning distinct regional species. (He totally thinks it’s fun.) Moving back to the Mid-Atlantic was a fairly easy transition, plant-wise.

In 2017, when Rob and his wife, Lia, moved into their new Northern Virginia home, their immediate goal was to, as Rob put it, “build up the landscaping with native plants.” Over time, the Ieras have expanded planting areas by reducing lawn, digging up unwanted weedy things and adding oodles of Virginia natives. They’ve converted their .2-acre property into a wildlife sanctuary—all the while keeping their neighbors’ aesthetics in mind.

The Plants

Rob chooses natives for the beauty they bring to his garden and for their wildlife value. Certainly, the corner planting alone could collectively support innumerable species of life: bumble bees and other native bees including oligolectic (pollen specialist) bees; plant-munching Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) caterpillars as well as their nectar-sipping adults (I calculated roughly 120 species of caterpillars are hosted in this planting!); birds such as hummingbirds, goldfinches, and other seed-eating avian friends; small adorable mammals; and so many other vital insects and their predators, too.

butterfly-weed (Asclepias tuberosa).

ruby-throated hummingbirds.

beard-tongue (Penstemon digitalis).

(Baptisia australis).

While this selection of plants would not be found growing together in a natural plant community due to their individual needs, these plants are certainly adaptable. Full or part sun is one of the criteria for success and so is well-drained soil.

And this is worth consideration: the plants that would most likely self-sow prolifically would be the Thimbleweed, Blue Wild Indigo, Black-eyed Susan, Foxglove Beard-tongue and Eastern Blue-star. “Volunteers” create an opportunity to share the bounty with friends and family (sometimes along with a warning).

The corner ensemble includes:

♦ Eastern Blue-star (Amsonia tabernaemontana) — This is a popular garden plant because of its habit and fall interest. The blueish star-like flowers haven’t emerged yet but when they do, they’ll attract butterflies and other flower visitors.

Cornell University Gardening: Willow Blue Star

♦ Culver’s-root (Veronicastrum virginicum) — The flower spikes add architectural drama to this grouping. Bumble bees and other insects are drawn to the pollen and nectar from the many tiny white flowers.

US Forest Service Plant of the Week: Culver’s Root

♦ Thimbleweed (Anemone virginiana) — Thimbleweed flowers attract small insect visitors. The handsome erect stalks and seedheads, seen here, stand out long after the white sepals have fallen. Later in the year, the “thimble” will mature to cottony fluff. Thimbleweed can self-sow prolifically.

North Carolina Extension Gardener: Anemone virginiana

♦ Northern Rattlesnake-master (Eryngium yuccifolium) — This Eryngium is found naturally growing west and south of Virginia; it’s rare in most Virginian counties. It could reach five feet in height. The pollen and nectar produced by the hemispherical flowers feeds butterflies, bees, wasps, beetles and flies. It’s the larval host for one moth species.

US Forest Service Plant of the Week: Rattlesnake Master

♦ Blue Wild Indigo (Baptisia australis) — Wild indigo is a long-lived perennial with a lovely rounded shape and pretty bluish-purple flowers (that have most likely bloomed at this point in time). It’s primarily pollinated by bumble bees. Baptisia is the host plant to at least 15 butterfly and moth caterpillar species.

The Natural Web: Butterflies Eat Their Peas

♦ Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) —This is a wonderful pollinator plant that’s also known to attract hummingbirds. Liatris hosts four caterpillar species and its seeds are consumed by birds. The striking flower spikes may need staking as they mature.

LBJ Wildflower Center: Liatris spicata

♦ Foxglove Beard-tongue (Penstemon digitalis) — The white flowers have faded and matured to seedheads that add interest throughout the year. Penstemons support about eight butterfly and moth caterpillar species, bumble bees and other insects, including one specialist bee.

The Natural Web: White Beardtongue for Pollinators

♦ Butterfly-weed (Asclepias tuberosa) — Butterfly-weed is such a carefree, long-blooming and low-maintenance garden plant. Longevity can be dependent on well-drained soils and a root crown that remains free of sun-blocking competition in the spring. Butterfly-weed is the host plant to the monarch butterfly (although not a favorite for egg-laying) and 11 other Lepidoptera species. The orange flowers attract a whole slew of other fascinating insects.

The Natural Web: Milkweed—It’s Not Just for Monarchs

♦ Scarlet Beebalm (Monarda didyma) — Hummingbirds, hummingbird moths, butterflies, caterpillars, native bees (including three specialist bees), seed-eating birds such as American goldfinches… all make scarlet beebalm a powerful addition to any garden.

Maryland Native Plant Society Wildflower in Focus: Bee-Balm

♦ Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) — Considered an annual or short-lived perennial, black-eyed Susans are a staple of many gardens. They support at least 16 Lepidoptera caterpillar species, many flower visitors and also a long list of specialist bees. Birds relish the ripened seeds.

Master Gardeners of Northern Virginia: Rudbeckia hirta

♦ Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) — Native grasses are essential to any garden and little bluestem, seen here too early in the season for developed seedheads, remains a not-too-tall staple. Plant it in enriched soil and the stems could flop. Little bluestem is the host plant to at least six caterpillar species—and the seeds feed hungry winter birds and small mammals. End-of-season mounds provide nesting sites for bumble bees the following year.

North Carolina Extension Gardener: Schizachyrium scoparium

♦ Maryland Wild Senna (Senna marilandica) — Growing up to four feet tall and possibly wider, this Senna requires some elbow room. The sprays of summer yellow flowers beckon hummingbirds and native bees, and the plant feeds up to eight butterfly and moth caterpillar species.

Cornell University Gardening: Wild Senna

♦ Tall Thoroughwort (Eupatorium altissimum) — There are many Eupatorium species to choose from and this one is adapted to drier sites. Eupatoriums host the most Lepidoptera caterpillar species of all the plants in this collection—at least 40. The nectar and pollen additionally supports native bees, moths, butterflies and other flower visitors.

University of Arkansas Plant of the Week: Eupatorium altissimum

What will inspire your plant choices?

The plants in this enchanting corner grouping are all perennials that can be commonly found at native plant sales, where Rob does most of his shopping. Many of his purchases are straight species and local ecotype plants. “While I have some cultivars on the property, I prefer the true natives. They seem to thrive better in the environmental conditions.”

Straight species, like those found in natural areas, have certainly evolved to be tough—and are smart choices for many reasons. Environmentalists caution that cultivars could be detrimental to the genetic viability of wild plant populations. As I see it, that’s reason enough to avoid them.

“People are complimentary…”

Not surprisingly, the Ieras’ wildlife oasis receives compliments from passersby. As Rob and Lia are out in the garden, they’ve welcomed neighborly interactions. “A few individuals have recognized the native plants,” Rob told me, “and it’s nice to take a break from working to share gardening stories.”

And no doubt, as the novel coronavirus continues to change our habits—pulling us outdoors and into our neighborhoods—native plant landscapes like Rob’s will inspire conversations and influence the front garden aesthetic.

I’m looking forward to my next drive-by double take.