RAT POISON KILLS A HELL OF A LOT MORE THAN JUST RODENTS

I inspected the tiny creature closely. It must have died recently, its brown and white furred body still soft and supple. Was it an outdoor cat that killed it? It certainly could have been. Free roaming cats have left quite a number of birds and small mammals for me over the years. But there didn’t appear to be any signs of trauma; no puncture wound and no blood. Hmmm. I dismissed the thought that this animal was poisoned—surely my immediate neighbors know that rat bait is a wretched solution? I left the mouse where it was, figuring it could be food for some other critter. Unfortunately, this was a mistake.

THE BIG LIE

Little thought is given to the other animals that live in

this mixed-use development.

SECOND-GENERATION KILLERS CAUSE SECONDARY VICTIMS

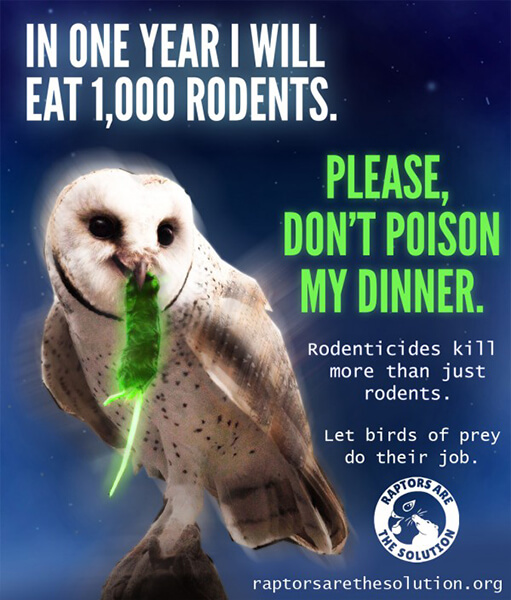

Today’s most widely used rat poisons are second-generation anticoagulants: highly toxic not only to the rodents that directly consume the bait but also to the non-target animals that eat the contaminated rodents.

Although the EPA has prohibited the sale of products containing brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difenacoum and difethialone directly to consumers, pest control companies and farmers are still allowed to use these second-gen anticoagulant rodenticides.

Like the first-generation of anticoagulants that preceded them, the “superwarfarins” prevent blood from clotting, induce internal bleeding and inflict a prolonged, painful death. However the newer poisons are many times more potent. “Second-generation anticoagulants,” the EPA explains, “are more likely than first-generation anticoagulants to be able to kill after a single night’s feeding. These compounds kill over a similar course of time but tend to remain in animal tissues longer than do first-generation ones.” This means that by the time the rodents die—five to seven days after consuming the bait—they can have up to 30-40 times the lethal dose in their bodies. Meanwhile, they stumble about and are easy prey for predators and pets.

Collateral poisonings of carnivores and omnivores alike are widespread wherever bait boxes are being deployed. The affected wildlife are more likely to get hit by moving vehicles, crash into structures or be killed by other animals. These non-target animals are also more susceptible to disease and vermin. In California, most coyotes, bobcats and cougars that die from mange—a skin disease caused by parasitic mites—also test positive for rodenticide exposure.

SOME FAST FACTS:

- Rodenticides are indiscriminate killers that attract and kill all kinds of animals, not just rats and mice.

- Second-generation anticoagulants are persistent and bioaccumulative; they remain in the victim’s bloodstream and accumulate in the liver.

- Non-target predators like foxes, coyotes, owls and hawks, and scavengers such as vultures, raccoons and opossums, suffer lethal and sub-lethal poisoning when they feed on poisoned rodents.

- Where second-generation anticoagulants are used, entire food webs are contaminated.

- By killing off the predators that would otherwise control rodents, anticoagulants actually generate rodent infestations.

- In one Canadian study of dead raptors, nearly 100 percent of owls had at least one anticoagulant rodenticide in their livers.

- Cats and dogs are also harmed from eating poisoned rodents.

The Centers For Disease Control receive about 15,000 calls per year from parents whose children have eaten rodenticides.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

- Residents, homeowners associations and business owners have the power to prevent rodent infestations and not resort to using rodenticides.

- Remove trash and food that attracts rodents to your property. This includes pet food, birdseed waste and compost piles.

- Plug holes and cracks leading to the interior of homes and other structures.

- Keep shrubs and trees trimmed and the foundation of buildings free of wood and junk piles that provide shelter to small critters.

- Remove invasive English ivy—it’s known to harbor rats. Replace it with native plants that support beneficial wildlife.

- Seek poison-free solutions to help reduce the market for poison.

LAST-DITCH OPTIONS?

- Snap traps don’t always kill instantly. If you plan to use them, never set them outside. Birds and other wildlife that help control rodents can be seriously injured. Check and empty the traps regularly.

- Do not use glue or sticky traps because they are cruel and can also catch other small mammals, birds and even reptiles and salamanders.

- And although drowning is not an ideal way to die, it could be a better alternative to other methods… And then there’s the “better mouse trap.” From Ted Williams’ article Poisons Used to Kill Rodents Have Safer Alternatives: “You take a metal rod, run it through holes drilled in the center of both lids of an emptied tin soup can so the can becomes a spinning drum. Fasten both ends of the rod to the top of a plastic bucket via drilled holes. Coat the can with peanut butter, and fill the bucket with water and a shot of liquid soap (to break the surface tension and thus facilitate quicker, more humane drowning). Mice and rats jump onto the can, and it spins them into the water. The first time I deployed the device in my New Hampshire fishing camp, it killed 37 mice between Labor Day and Thanksgiving.” To avoid killing other small mammals, set this device indoors.

If you are considering a trap and release, please read Nancy Lawson’s article Stranger in a Strange Land before you do.

For more information:

The Humane Society—What to do About Wild Mice

PETA—Living in Harmony with House Mice and Rats

Scientific American—Blood Thinning Rat Poison is Killing Birds Too

Raptors are the Solution—Alternatives & Tips

Safe Rodent Control—Risks for Wildlife

BIRC (Bio-Integral Resource Center)—Protecting Raptors From Rodenticides

Audubon—Poisons Used to Kill Rodents Have Safer Alternatives

Environmental Protection Agency—Controlling Rodents and Regulating Rodenticides

Updated 2/8/2018